Historically, we have seen areas suffering from social upheaval produce revolutionary art scenes. Berlin in the 1920s, ravaged by unfathomable inflation, upended the artistic lexicon with the advent of BauHaus. Marred by dust and rampant unemployment, the Dust Bowl, Great Depression era in the Southwestern United States produced paramount artists like Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger. When unable to make sense of their thoughts and crumbling environments, artists work to give physical form to the turmoil they and their communities experiece.

Berlin in the 1920’s

Following the disastrous loss of WW1, Germany had an identity crisis. The monarchy and efficacy of Imperial Germany were called into question, and subsequently, the country underwent revolution. Kaiser Wilhelm was overthrown along with the traditional and militaristic values of old, anda far more ambitious political endeavor rose in replacement: the ever-democratic Weimar Republic. The newfound parliamentary democracy permitted all citizens over 20 years old, including women, the right to vote and hold office, instantly identifying itself as one of the world’s most democratic countries.

However, the project quickly lost its footing; Weimar’s economy struggled almost immediately. Unable to escape the debts allotted by the Treaty of Versailles, combined with the Reichstag’s inability to pass appropriate legislation, led to inflation, with the monthly inflation between August 1922 and November 1923 rising to 322%. For reference, “at a monthly rate of 50 percent, an item that cost $1 on January 1 would cost $130 on January 1 of the following year.”

Despite the hope driving the Weimar project, Berlin suffered tremendously. Decimated by austere levels of unemployment, activities once confined to the shadows were now embraced in broad daylight. Unabashed endorsements of sex work, violence, and voyeuristic pleasure shook Berlin to its core.

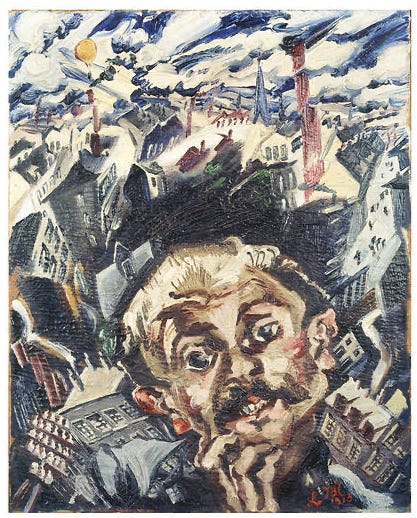

Yet, the artistic expression permitted by the Republic was astounding. In the face of such dire circumstances the artistic scene took off, bending the artistic realities that the country and Europe were previously accustomed to. Amongst the various artistic inventions of the 1920’s like Postmodernism, Dadaism, and the invariable founding of the “BauHaus,” was Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity, Within New Objectivity, a branch of Realism took force, named Verism. Verism was characterized by subject focused portrayals of the various cast of characters one could find in Weimar Berlin. Sex workers, drug addicts, transvestites, ‘respectable’ businessmen, lawyers and public officials. These portraits were created to “hold up a mirror to the rootless, doomed society of Weimar Germany.” As Berlin struggled to rectify its own identity in the volatile Weimar Germany, Modernist artists like Otto Dix, Max Beckmann, and George Grosz strove to make physical the collective sense of dread pervading Weimar Germany. In their efforts, monumental advances in the artistic scene marked 1920’s Berlin as a hub for artistic exploration, evolving the artistic lexicon forever.

Southwest United States in the 1930’s

Best encapsulated by Woody Guthrie’s famously embellished autobiography, Bound For Glory, the Southwest United States in the Great Depression and Dust Bowl Era was a hot-bed for the burgeoning genre of folk music. Following the stock market crash of 1929, horrific droughts struck the United States, resulting in dust storms of the “Dust Bowl.” In 1930, many Southwestern Americans found themselves without a job, and took to the road. Many of these Americans, specifically those in Oklahoma, fled the scorched Southwest and ‘rode the rails’ in the hopes that the fields of California would lead to steady pay and a decent life. Life was on edge and unpredictable, and. the harsh reality of California was far less welcoming than the imagined Garden of Eden that many ‘Okies’ and Southerners envisioned. Woody Guthrie’s describes this very phenomenon in “Do Re Mi,” singing:

Lots of folks back East, they say, is leavin' home every day

Beatin' the hot old dusty way to the California line

'Cross the desert sands they roll, gettin' out of that old dust bowl

They think they're goin' to a sugar bowl, but here's what they find

Now, the police at the port of entry say

‘You're number fourteen thousand for today’

The hardships presented by the economic disaster plaguing Southwestern Americans festered into a deep hurt that only music could convey. Folk music gave many Americans the chance to vocalize the heartaches they carried; uprooted families, lost jobs, or leaving home just to find opportunity,. Therefore, a guitar around a campfire or ina congested railroad car was a sweet touchof respite. Folk music containing voice inflections in songs by esteemed artists like Huddie William Ledbetter, or “Lead Belly,” and Pete Seeger exemplified the anguish suffered by those living in southwest America. Oscillations in the near voice cracks in these songs almost evoke a sensation that these artists were choking on emotion; bleating lyrics about economic hardship and the hunger forced upon them. In the face of starvation and a life many deemed not worthy to live, creatives decided to express the inner turmoil through picking guitars and releasing their torment through song. Folk music was indelibly marked by many artists' personal experience with vagrancy and poverty, resonating with many southwestern Americans facing the same grievances.

Chicago in the 1950’s

When one reads Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, what cannot be missed is the eclectic nature of Chicago in the 1950’s. Down every street, one could stumble into an establishment, and you could find yourself in one of Chicago’s blues clubs. The scene had already taken form, spearheaded by legends like Muddy Waters and Howlin Wolf, and Buddy Guy.

What are the blues? Blues legend Lightning Hopkins described it as something so difficult to pin down, like “death,” but it is whenever “you get some sad feeling, you can tell the whole round world that you got nothing but the blues.” For blues artists, ‘some sad feeling’ could be any number of hardships accumulated in one’s life, whether it be a cheating partner, being unable to find a job, or just a plain broken heart.

Songs like The Things I Used To Do by Guitar Slim evoke the guttural, yet soothing croons of classic blues songs. Although the blues evolved further as revolutionizing artists like Buddy Guy continued to push the envelope, the consistent messaging that the blues could only derive from the geyser of one’s soul erupting with such emotion that mere words could not do; only the heartrending yelps and wails of blues music would suffice. As many blues artists in the 50’s worked meager odd jobs, or even teetered on the verge of homelessness, performances gave the stage to the artists’ and era’s trials. Only with unceasing collisions with poverty, discrimination, and personal troubles, could blues artists make physical their hardship into soul-rupturing records.

Wealth and Art

The financial means to apply oneself to their creative enterprises without the worry of economic stress can undoubtedly be an advantage. This argument may be difficult for those who hold creative expression to be synonymous with wealth and privilege. The time needed for serious exploration of a given historical topic or legitimate mastery of an instrument is typically not feasible for most working people. Therefore, one could reasonably make the assumption that the most prolific members of prominent art scenes are those with the means to fund their creative enterprises. Or, alternatively, that artists must be commissioned by those with the means to pay for such work, like Italian aristocrats commissioning work from Da Vinci and Michaelangelo in Renaissance Italy. Additionally, one could extrapolate that there is no special connection between impoverished areas and an explosion of art, as we have seen inspiring and monumental art produced by artists in regions flush with wealth.

However, the thesis does not argue that the only artistic scenes that we have seen thrive are those in areas of great destitution. Yes, wealthy artists (especially those commissioned by the bourgeois classes,) have greater time, resources, and finances to pursue their artistic endeavors. Therefore, it is clear that some wealthy areas and wealthy artists throughout history have produced challenging and inspiring art. Nonetheless, these two are not mutually exclusive. Revolutionary and innovative art can have various inspirations, and destitution and wealth are two instances on the opposite ends of the spectrum, representing two separate breeding grounds. Financial resources grant artists the time, space and connections to explore the depths of their creative being. Conversely, lack of financial resources leads one to being unable to find an immediate solution to the most basic problems. Moreover, the broader community of an artist being unable to rectify itself leads to further internal collisions. If the society I am supposed to entrust in can’t bring itself together, what hope is there for my being? However, such moments of introspection and inquisition such pushes artists to explore the depths of their creative being to find light and understanding where there previously was none.

Fostering Creation from Calamity

Art results from creatives being unsatisfied with their thoughts, feelings and desires merely existing in conversation or taking hold in their mind. Spilling over into reality, artists are driven to find expression in what weighs so heavily upon them. Artists are confronted with day to day realities that are far too much to hold in one’s being in areas and communities ravaged by political turmoil and economic anguish. These experiences must be made physical, into art one way or another. Creative communities push even further to make sense of the undefinable when confronted with the mind-bending difficulties of poverty or overall societal collapse.