A Christmas Carol: The Past, Present, and Future of an Iconic Novel

The Role of a Christmas Carol as Protest Literature and Escapist Fiction

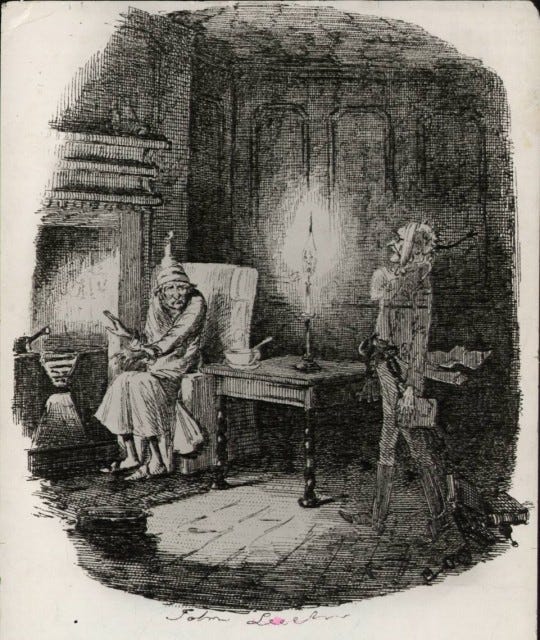

Retail stores across the country are blasting holiday classics over their speakers at full volume. The tree has been decorated, the mistletoe hung, the garlands strung, and the presents tidily wrapped and waiting for that joyous morning. Many Americans will settle in to watch a traditional Christmas movie or even curl up with a book. One book stands out as one of the most popular pieces of Christmas literature in history, not including the Biblical story itself: Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. While many modern consumers may immediately think of its numerous adaptations, including the animated 2009 Disney movie and the childhood favorite Mickey’s Christmas Carol, the original text stands out as a beacon of hope and a call for change, both in Dickens’ time and our own. A Christmas Carol is one of the most enduring stories of the 19th century and spotlights many issues that are still relevant today, including poverty, exploitation, consumerism, and inequality. This review will analyze the role of A Christmas Carol as protest literature in the 1800s, explore ways this dynamic story applies to social issues of the present day, examine how new mediums of the story entertain modern themes, and finally, dive into the novella’s vision of the future.

The Novel of English Past

Charles Dickens grew up in the 19th century at a turning point in English history. Religion was still a powerful influence on the culture and politics of the country, and several pervasive attitudes about the poorest segments of English society were rooted in traditional Christianity. Many members of the Church of England believed that poverty was a direct result of moral failing; it was seen either as a punishment from God or a test of character. Reverend Thomas Gibson wrote scathingly on the topic: “The late and present distress of the manufacturing population of Great Britain must be deemed, in the case of multitudes, in a very considerable degree, attributable to themselves … in prosperous times of trade, the habits of the operatives are very commonly deserving of the severest reprehension. They are marked by idleness, selfishness, extravagance, and brutish intemperance.” However, with industrialization on the rise and underpaid factory workers massing England’s urban centers in larger numbers than ever before, Dickens called attention to hideous working conditions and worker exploitation in many of his novels, including Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, and of course, A Christmas Carol. Many of his writings also feature religion as a central theme. His criticism of a capitalist society in A Christmas Carol may arise not in spite of his religious views, but because of them. His advocacy for change aligns strikingly with the emergence of a Christian Socialist Movement in the early 1800s, which advocated for the working class and called for the Church to be an agent of change.

Dickens’ call for change can be seen most clearly in his vivid and unflinching description of poverty. A Christmas Carol in particular sketches a haunting picture of what poverty looked like in Dickens’ time:

The ways were foul and narrow; the shops and houses wretched; the people half-naked, drunken, slipshod, ugly. Alleys and archways, like so many cesspools, disgorged their offences of smell, and dirt, and life, upon the straggling streets; and the whole quarter reeked with crime, with filth, and misery. (Page 72)

But the famed novelist goes farther still, crafting a poignant literary rendition of destitution by representing poverty as two starving children clinging to the robes of the Ghost of Christmas Present:

From the foldings of its robe, it brought two children; wretched, abject, frightful, hideous, miserable…Yellow, meagre, ragged, scowling, wolfish; but prostrate, too, in their humility. Where graceful youth should have filled their features out, and touched them with its freshest tints, a stale and shrivelled hand, like that of age, had pinched, and twisted them, and pulled them into shreds. Where angels might have sat enthroned, devils lurked, and glared out menacing. No change, no degradation, no perversion of humanity, in any grade, through all the mysteries of wonderful creation, has monsters half so horrible and dread. (Page 66)

Dickens doesn’t stop by pointing out the horrors faced by England’s working class. He begins his novel by creating a character so stingy and unlovable that his infamy would last more than a century: Ebeneezer Scrooge. In the very first chapter, the same one in which he bestows some of the worst traits of the human race on his character, Dickens references some controversial issues of the time and sets his despised Scrooge firmly against the working class. When a man enters Scrooge’s place of business to ask for a charitable donation to the poor, Scrooge replies:

Are there no prisons?...Union workhouses?...The Treadmill and the Poor Law are in full vigour, then? (Page 12)

The Poor Law of 1834 placed the poor in workhouses, where they were fed and clothed but forced to work many hours a day. Even worse, prisons—which, similar to modern prisons, primarily held low-income members of society—began to employ the Treadmill as a punitive measure. Similar in function but much more sinister than the present-day exercise machine, these human-powered mills were created to “reform stubborn and idle convicts.”

By connecting some of the most brutal practices regarding the poor with a despicable tyrant, A Christmas Carol mercilessly criticized English society and government of the time and what it would continue to be later on. But the subsequent reformation of the main character is an even more powerful illustration.

He became as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world. (Page 91)

By concluding the story with a significant positive change in such a seemingly hopeless character, Dickens represents how the city, the nation, and the world he lived in could see a similar transformation occur. This is Dickens’ vision of a better society, where the kind and generous atmosphere of Christmas remains all year long. Because of this, A Christmas Carol transcends its role as a sweet holiday story and reveals itself for what it is: an important piece of protest literature.

The Novel of American Present

The story’s adaptation into new mediums have allowed it to survive and thrive in modernity. Different interpretations have given it new life and new meaning. While A Christmas Carol was written to illuminate issues from the 19th century, it remains relevant in an entirely different time period, culture, and geopolitical climate because the social problems that underlie A Christmas Carol have survived into the 21st century.

Adaptations of the story began coming out soon after its publication. In 1843, the same year that A Christmas Carol was published, "A Christmas Carol; Or, The Miser's Warning!", a play by C. Z. Barnett and Charles Dickens, was performed on stage. Dozens of stage adaptations have since seen success. The first film adaptation, Scrooge; or Marley's Ghost, was a silent black-and-white film produced by R. W. Paul and directed by Walter R. Booth in 1901. Numerous films have since transformed the classic Christmas story into a contemporary interpretation. The 1988 comedy Scrooged features a modern American businessman (Bill Murray) as Scrooge and draws on themes of greed, consumerism, and ruthless ambition. Starring Susan Lucci in 1995, Ebbie was the first adaptation to feature a female Scrooge. Scrooge and Marley, starring David Pevsner as Ebeneezer in 2012, became the first version to include gay characters. In this way, the premise of the original story has been used as a vessel for a number of relevant issues today.

However, some of the story’s original themes translate perfectly across the centuries. One of the most recurring issues in A Christmas Carol is poverty. Dickens uses compelling imagery to show the effects of poverty on several characters, including Scrooge himself, who spent much of his childhood in a “poorly furnished, cold, and vast” boarding school. But the story calls on a reader’s keenest sense of compassion in the introduction of another character affected by poverty, proclaimer of the novella’s most famous line, Tiny Tim. The crippled son of Scrooge’s clerk, Bob Cratchit, Tiny Tim is widely considered one of the most heartwarming characters in A Christmas Carol. There are many conjectures as to what his fatal illness might have been, including rickets, tuberculosis, or cerebral palsy, all of which disproportionately affected the poor population of England and would have been exacerbated by malnutrition.

Childhood poverty is still a serious global issue. In 2021, the UK saw an almost 20% increase in child poverty. This issue also widely affects the United States. In 2023, approximately 11.4 million children were living below the poverty line. That year, the official poverty line was $30,900 for a family of two adults and two children; that is, $7,725 per family member per year. Studies have shown that the stress of economic hardship has a long-term physiological impact on children, significantly increasing the risk of chronic diseases and mental illnesses over time. Additionally, young children in economically insecure families score lower in language development and other measures of academic success, which affects their education and career prospects throughout their life. Lost productivity, increased health care costs, and other expenditures caused by child poverty are estimated to cost the United states $500 billion to $1 trillion per year.

Hand-in-hand with A Christmas Carol’s message about the detrimental effects of poverty is a subtle plea for legislation to improve the lives of the poor. While this was directed at the 19th century English government, there are plenty of reasons to repeat it here and now. In 2021, pandemic relief-measures like increased child tax credits reduced the number of children in poverty to a record low of 5%, lifting 2.9 million kids above the poverty line. When these policies expired in 2022, child poverty more than doubled, reaching 12.4%. But the temporary policies proved that it is possible to significantly reduce child poverty with legislation. Charles Dickens’ centuries-old call for change is still as necessary today as it was while he was alive.

The Novel of a Brighter Future

A Christmas Carol is not limited to social criticism, but stands as a beacon of hope for the future. Although the novel takes the reader to dark places, from Tiny Tim’s death, to Scrooge’s confrontation with his own mortality, to the question of what makes life worth living, it concludes with a message of warmth and reformation, cheerfully displaying a vision of the future where no child dies in poverty and no one withholds their generosity. By transforming one of literature’s ugliest characters into a kind, joyful soul, Dickens shows us how the world could be, and that’s a vision that many Americans need more than ever.

The story still has a place in modern society, not just for its political messaging but for its light-hearted tone and themes of hope in hard times. While there are tragic moments in this story, there are also moments of joy that can’t fail to raise a reader’s spirits. The Ghost of Christmas Present brings Scrooge to a destitute mining town, where a family of people who do back-breaking work for almost no pay sing Christmas hymns as gladly as if they had the whole world in their pocket-books. Immediately after, the spirit whisks Scrooge out to sea, where lighthouse keepers wish each other ‘Merry Christmas!’ in spite of their cold, lonely occupation. Finally, the classic scene at the Cratchit dinner table is a warm representation of family love, a scene which can snatch a reader from whatever troubles occupy them in reality and invite them to share in the laughter and joy.

The most powerful message of hope in the story lies in its image of the future. The portrayal of the future in A Christmas Carol, an ominous shadow that is always looming but never seen, is one that many modern readers may share.

It was shrouded in a deep black garment, which concealed its head, its face, its form, and left nothing of it visible save one outstretched hand. But for this it would have been difficult to detach its figure from the night, and separate it from the darkness by which it was surrounded. (Page 69)

The Ghost of Christmas Future is a harbinger of the story’s most sinister moments. It takes Scrooge through the most impoverished streets in London, a scene of grief in the Cratchit home, and the site of his own grave. The Ghost of Christmas Future strikes terror into Scrooge in the same way the future terrifies many individuals today. But A Christmas Carol is a reminder that it is never too late to create change in the world; it contains a promise that a positive version of the future is possible. The message of hope in this novel can inspire the change Dickens was seeking in his time. The conclusion of A Christmas Carol leaves readers with a sense of hope that neither time nor hardship has managed to efface:

He became as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world… and it was always said of him, that he knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge. May that be truly said of us, and all of us! And so, as Tiny Tim observed, God bless Us, Every One! (Page 91 and 92)