A Tale of Two Cities

A Reflection on How Diverging Uses of Public Transportation Affects Communities

When someone thinks of public transportation in the United States, it’s rarely in a glorified way. Beyond the lofty aspirations of expansions, connecting cities to one another, considerations of public transport are mundane.

As part of the reality of our daily lives, public transportation is supposed to play its part. There is no expectation of amazement; just facilitating our movement. Only when it fails or impedes this core requirement does it garner our increased attention.

No other form of public transportation exhibits this banal existence more than the bus system. Buses lack the star power of other methods. Metros and tramlines are fast and direct; larger trains possess amenities and can travel long distances; planes and boats traverse unique areas. This leaves buses in an unfortunate area. Dominated in a realm of personal travel, the antithesis of public transportation, buses often struggle to define their necessity.

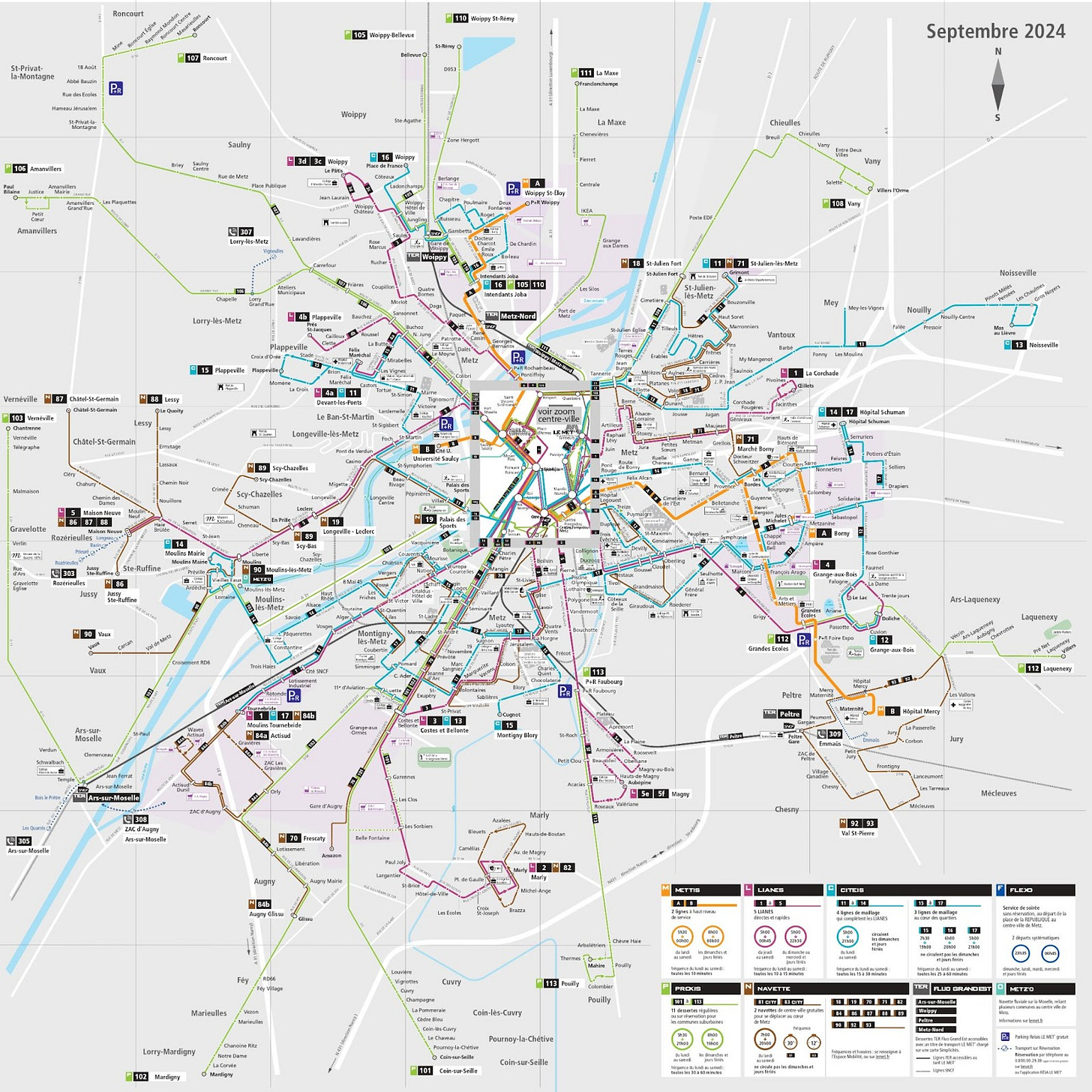

Yet, in France, the car’s dominance is diminished, and the bus has taken advantage of this opportunity. Cities nationwide have comprehensive bus systems stretching out into their outer communities. Metz, France, my home base this fall semester, is no exception. After a couple of months of traveling across Europe, the bus system was always the first and final part of my trip. This reliance grabbed my attention and shifted how I viewed the bus. Hence, I decided I would try to take every single line on the system.

After a month and a half of spending my weekends crisscrossing the Metz metropole on 40 unique bus lines, I have experienced firsthand why European public transportation is overall successful. While I will not dive into the minutia, (I have actually already done so in a YouTube video), several overall trends demonstrate the utility the system creates.

For example, instead of designated school buses, most students, from elementary to university, use local public transportation systems to go to school. In addition, students have multiple-hour lunch breaks, often returning home midday before returning to school, and student ridership is consistent throughout the day. Similarly, many commuters travel into the city each morning before returning in the evenings. These two passenger bases supply a consistent ridership to the system, further supplemented by travelers and other less-common passengers. To support these targeted riders, the system largely employs a hub-and-spoke transport model, where lines originate at principal stops within the center city before branching outwards to the outer edges of the metropole. The model reduces system complexity by minimizing the number of lines needed to connect each stop. To further improve the bus system, Metz has begun to add more wheel lines, lines used to connect stops and other lines outside of the main hubs. These changes are all part of the large-scale project to revitalize Metz’s public transportation.

The crowning achievement of the revitalization project is the M line’s trambuses. These trambuses have designated lanes and streets, spacious bus stops, and large-capacity carriages. They have become the backbone of the bus system, running as frequently as every 10 minutes during midday. The hybrid design allows these lines to bypass traffic conditions in their own lanes while possessing the capability to snake through Metz’s older, narrow streets, which helps reduce project costs and the impact on Metz’s urban geography.

These efforts have been rewarded by high ridership. As of 2021, 228,999 people lived in the Metz metropole area; yet in 2019, 23,426,000 passengers used the Metz bus system. For comparison in the United States, Atlanta’s MARTA (Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority) bus system recorded 50,018,300 passengers in 2019. (2019 statistics are being used, due to both cities having yet to recover fully from the decreases caused by Covid-19). Yet, as of 2020, the 3 counties MARTA serviced by bus (Fulton, Clayton, and Dekalb) encompasses 2,128,687 people. When comparing the ratio of annual riders to population, Metz’s score of 102.297 monumentally exceeds Atlanta’s, over quadrupling Atlanta’s ratio of 23.497. All the while, Metz’s serviced population is just ~11% of Atlanta’s.

The Metz bus system reflects a greater scope of possibilities served by European public transportation. Across the continent, cities large and small are robust, amply meeting the transport needs of their citizens. In return, these citizens positively support the costs to maintain and grow these systems.

While these statistics demonstrate a comprehensive success for Metz’s transportation systems, they underscore a grim truth about America’s public transportation systems. A microcosm of the United States’ history, Atlanta’s relationship with public transportation has been tenuous. Ideas about public transit systems began in the 1950s, but it was not until the 1960s that the ideas became a possibility. However, due to racial prejudice, political opposition, and Georgia’s rural-urban divide, the transit system sat in limbo, facing nearly a decade of failed state and local referendums, until finally passing in Fulton and Dekalb counties in 1971. Originally encompassing a much greater scope, the suburban rejection of the project has truncated the potential for MARTA to successfully connect the region, leaving a gap. This is not just an old problem. While Clayton County approved a contract with MARTA financed by a 1 percent sales tax in 2014, both Cobb and Gwinnett Counties have continuously rejected similar plans, even as recently as November 2024.

Atlanta’s story is not unique; Americans do not find value in funding public transportation. Except for Washington, D.C., the few modernly successful non-bus rapid transport systems (i.e. subways) all predate the Ford Model T and the public’s adoption of automobiles into their daily lives. These two industries both claimed first-mover advantages, continuing to establish influence over the geographic scope for decades. While many of the largest Western European cities had public transportation systems by 1920, the same could not be said for American cities, establishing diverging opinions and cultures on public transport. A few decades later, the passage of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 by Congress created a nationwide network of reliable, long-distance roads, further cutting into the rail market. Thus, both long and short-distance public transport were seen as inviable in comparison to personal, individualistic methods.

Local public transportation appears to have followed a similar fate to the American rail service. Though, notably, while federal policymaking led to the decline of rail transport in the United States, it may be the key to its revival. In 2021, the momentum for increasing funding for public transportation reached new modern heights. Led by President Biden, a career advocate of public transportation and famously known to have commuted between Washington D.C. and Wilmington, Delaware each night during his long senate career, Congress passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. The act allocates over $66 billion to Amtrak, the country’s national passenger rail service. Increased funding has reminded Americans of the viability Amtrak possesses, setting an all-time high annual ridership in 2024 of 32.8 million passengers, quickly recovering from the COVID-19 dropoff.

Amtrak is now facing renewed competition in the rail market, as Brightline, a private company that operates high-speed intercity rail, has begun service in Florida. The company has shown promise, registering almost 2.5 million annual passengers from November 2023 to 2024. With an additional expansion under construction between Las Vegas and the greater Los Angeles area, the increased competition may indicate new market opportunities in the industry long held solely by the government-owned monopoly.

Public transportation advocates are hopeful to extrapolate these recent successes with other forms of public transit, and for good reason. The advent of globalization has brought along a level of connectedness previously unseen. An American can now watch those traveling on a metro in Paris, a bus in London, or a high-speed train in Tokyo, all from their fingertips. This spread of information has challenged the existing notion of car-centered transportation, demonstrating an increasing level of dissatisfaction with the U.S. status quo.

Public transportation has ingrained itself into the public's psyche on the European continent, allowing for the continuous and stable growth of its transportation systems. In comparison, American systems were usurped by the development of automobile infrastructure. Today, the United States has begun to make up lost ground but remains heavily dominated by cars. For the United States to continue improving, it must educate the population about the utility public transportation brings into a community. Hence, it is pivotal that we change how we talk about and thus think about public transportation. No longer should we use public transportation as a means to an end. After riding 40 different bus lines in the last few months, my greatest takeaway is that the journey can be as, or even more, valuable than the destination. So, next time you find yourself using public transportation, take a minute to appreciate its amazing capabilities that help your journey.