If you have kept up with the headlines for foreign relations within the last few months, you may have noticed tariff threats as a recurring trend. Nestled into them, however, the Trump administration has been keen to focus on one thing: access to rare earth elements (REE). It is not difficult to understand why there has been such a shift in focus towards these elements; many modern technologies, including smartphones, electric vehicles, or even advanced military defense systems, require the elements for manufacturing. Their control has become a new form of global power struggle—one in which the United States finds itself increasingly vulnerable. This increase in focus is not just about securing a supply of materials but about maintaining economic leadership, technological superiority, and national security. Hence, with the increased proliferation of computing technologies, rare earth elements have increasingly cemented themselves within the United States' economic and foreign relations.

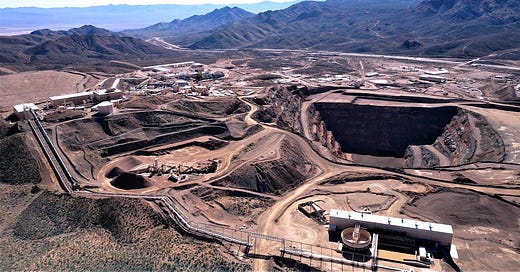

During the 20th century, rare earth elements remained niche, as their utility was limited to specialized scientific and industrial applications. However, following the third wave Industrial Revolution into the information age, the demand for REEs skyrocketed. The United States, once a leader in REE extraction with California’s Mountain Pass mine, saw its dominance erode as its competition with China increased. During the beginning of the Chinese economy’s rapid development in the 1990s, the Chinese government identified an opportunity and invested heavily in the sector, implementing the 973 program in 1997 to capitalize on the resources in the country. Today, the country controls over 60% of the world's production of REEs. As such, this shift has placed global technology industries at Beijing’s mercy, creating a resource dependency that threatens the status quo of modern technological development.

Notably, these are not empty threats by China, as the country has demonstrated a willingness to flex its economic muscle. In 2010, following a diplomatic dispute with Japan, Beijing abruptly cut off REE exports to the country. Japan, a leading manufacturer of sophisticated technological products like automobiles, was left scrambling for alternative sources. Despite filing a complaint at the WTO and winning the case against China in 2015, the REE embargo forced Japan to reevaluate its procurement of these materials and reduce its dependence on China.

As cases like this become increasingly common, the economic implications of REE dependency are profound. REEs have become political bargaining chips, akin to the use of oil in the 1970s. The United States, which currently imports nearly all of its REEs, faces a stark reality: without securing its own supply chains, it remains vulnerable to geopolitical coercion.

Efforts have been made to revive domestic production, by resuming operations at the Mountain Pass mine; however, the refining capacity remains overwhelmingly Chinese-controlled. Furthermore, the stakes are continuing to rise for industries, even beyond electronics. For example, the U.S. automotive industry, as it shifts toward electric vehicle (EV) production, faces severe risks as many EV motors rely on REE-based permanent magnets. If China continues to restrict exports, current U.S. production would be unable to meet automakers' demands for materials, and those producers may be forced to seek expensive alternatives or slow production entirely, which could mirror the kind of economic stagnation seen during the 1973 oil crisis. As such, because of U.S. wishes to safeguard its economic independence, investments in domestic mining and alternative foreign options have become a national priority.

Expanding beyond economic concerns, the geopolitics of rare earth elements are redefining international alliances. Towards the end of 2024, the Biden administration reached an agreement with Ukraine to secure access to its REE deposits in exchange for military aid. However, Ukraine, following the U.S. presidential election, delayed signing the agreement until Trump took office to allow him to take credit for the deal in exchange for goodwill. However, with the current deteriorating relations between Trump and Ukrainian President Zelensky, Trump has changed the demands of the agreement to further secure more concessions from Ukraine. While these negotiations are still in process and details fluctuate rapidly, the fact that the deal is at the forefront of U.S.-Ukraine relations, despite the Ukrainian mineral industry being a minuscule fraction of its economy, signifies an increased desperation by the United States.

Importantly, other countries are beginning to posture themselves as opportunities for industrialized countries, like the United States, to obtain rare earth elements in exchange for political and militaristic support. In January 2025, M23, a Rwandan-backed paramilitary group, launched an offensive in the eastern regions of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), capturing large swaths of the North and South Kivu regions. The DRC has immense mineral natural resource deposits throughout the country, including over half the world’s known cobalt. In the occupied regions, M23 rebels have begun illegally exporting Congolese minerals to Rwanda to sell on the global market. Rwanda is resource-poor in comparison to the DRC. Despite that, the country signed an agreement with the European Union (EU) in 2023 to improve critical mineral exports between the two parties. Rwanda appears satisfied to willingly violate the sovereignty of the DRC to further control the flow of these valuable minerals to increase its geopolitical power. As such, members of the EU Parliament want to suspend the agreement to further prevent Rwandan exploitation. On the flip side, Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi has publicly offered the United States and EU increased access to the Congolese minerals in return for militaristic and economic support. Viewing the conflict in the DRC as a parallel to that of Ukraine, the Congolese president is capitalizing on his country’s resource advantage. While the Congolese mineral exports are not specifically REEs, the possession of desired mineral resources presents an increasing opportunity within the developing world to extract greater concessions from industrialized countries. As more developing countries begin to recognize the strategic geopolitical implications of possessing any mineral reserves, especially scarcely mined ones like REEs, their bargaining power will increase as technological innovation stalls in developed countries without access. Hence, the U.S. and other developed countries are striving to secure prolonged access to these reserves before they are shut out.

Despite advancements in mining rare earth elements, they are set apart from other strategic resources due to the complexity of their extraction and processing. Unlike oil, which can be drilled and refined with relative ease, REEs are dispersed in low concentrations, requiring complex chemical processes to separate the different elements into usable forms. China’s dominance within the industry is not merely due to vast reserves but to its immense investment in refining capabilities, which now consist of 85% of the world’s capabilities. As a result, the refinement of REEs remains a bottleneck for any nation seeking independence from Chinese supply chains. For the U.S., the challenge is not just about securing raw materials but about regaining lost industrial capabilities from decades of outsourcing. Additionally, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has facilitated new mining deals in Africa and South America, ensuring Beijing’s grip on REEs extends beyond its own borders. Now the United States and its Western partners must catch up. Beijing’s near-monopolized control over both the mining supply and the refining process has empowered the country. Export restrictions on REEs now loom at the forefront of American-Chinese trade relations, which continue to be impacted as the trade war between the two countries heats up again. As a result, the U.S. is scurrying to find alternatives to its China problem.

Currently, the United States stands at a pivotal moment. The rare earth element race has evolved beyond an economic issue into a defining challenge for national security, technological innovation, and geopolitical stability. Without decisive action, the U.S. risks falling further behind in the global resource competition. To counter China’s dominance, Washington continues to pursue investments in domestic production and forge strategic international partnerships. Cognizant of the power that oil availability held during the 20th century, American leaders are working to prevent being cut off from rare earth elements. Countries are beginning to acknowledge that secure access to REEs will not only control the future of technology but will reshape the geopolitical order. Failure to act will leave the U.S. at a strategic disadvantage, subject to economic disruptions and geopolitical pressures dictated by an increasingly assertive China. So, keep an eye out for most headlines; there is plenty more to come.